The End of the Bloodiest Holy War, Part II

Disclaimer: I’m not by no means a Python expert. As a general rule, take everything with a grain of salt.

This is a somewhat long post, take your time.

The first part dealt with the problem to be resolved.

In this part, the foundations of a ficticious plain text editor are put in place.

Prefatory clarifications

First and foremost, this is an imaginary exercise, and not a real text editor. It is this way to illustrate the problem through the lens of a unconventional editor which knows nothing about it.

Second, you may wonder why I’m interested in creating Yet Another Text Editor. After all, I said special tools are not the solution. Well, they are not, but:

-

This not qualifies as a special tool. It is about handling plain text. The goal is to infer and generalize a collection of principles meant to be applied to existent and new text editors.

-

Of course, it has to be a language-agnostic editor. I am not trying to suit Anyone’s Language (or a programming language at all), because that would’t be general.

It should be useful even to write a shopping list (as long as it can be beautifully written thanks to a damn good text editor).

From the beginning, I will discuss an impossible version (due to technical issues), and seemingly incompatible with every piece of plain text in the world. I know that. But at the end, you will find how all this is not so ficticious after all 😉.

Let’s begin.

Asumptions

- Spaces and tabs are not indentation (‘Heresy! Burn him at the stake!’).

- Newlines can be *represented as:

- The newline character

LF(U+000A). - The newline grapheme

CR(U+000D) +LF. Order matters.

- The newline character

- By (POSIX-like) definition, a line must end with a newline. Without it, lines are incomplete.

- I will use the term ‘buffer’ instead of ‘file’ (because you know, text is not always read from/written into a file).

* Preferably using just one kind of newline per buffer. Consistency, pal…

I also will consider each buffer as if it were about to be ‘blindly’ concatenated with more text at both ends, which means:

-

If the buffer is not empty, is expected to end with a complete line (and hence a newline).

-

The first character in the buffer (offset 0) is located after a (imaginary) newline (at the end of the text block after which this will be concatenated), so it will be treated accordingly.

-

By definition, an empty file has no broken nor full lines. Concatenating it is a ‘no-op’ (*which actually is the intended behaviour).

* Unix tools like

catare not aware of text, just bytes. In the unix world, general tools are highly apreciated, which explains the POSIX’s definition of lines.For example, consider how

wc -l <file>treats final newlines and broken lines. Note how this is very handy if you have to implement a text-based tool.Interoperability is king.

Without further ado:

Indentation without spaces nor tabs

If this text editor is as naive as others, we need something naive to represent indentation. In other words: whatever we provide, the editor must be inclined to consume it with such semantics that the text behaves as we expect.

As normal text editors does the ‘wrong’ thing, and indentation is not reliable, some programming languages add curly brackets as backing:

// K&R style.

int main()

{

printf("Hello, world!\n");

if (foo()) {

bar();

// ...

}

}

Let’s borrow the essential idea. Basically, we need two new control characters:

- The ‘open indentation level’ (or

OIL) character. Will be denotated as ►. - The ‘close indentation level’ (or

CIL) character. Will be denotated as ◄.

Most of control characters are in use, even when some of them are remnants of the good old days. We cannot just repurpose two of them and get away with it, but let’s say we pick two with care, like:

- Private Use 1 (

U+0091, a.k.a.PU1) as ►. - Private Use 2 (

U+0092, a.k.a.PU2) as ◄.

This way, every OIL character must be paired with a following CIL character. Once a level is opened, the following lines in the block does not need to carry any character around for indentation: they are just enclosed. Even in multibyte representations, the space-saving is unquestionably good (but we do not care about this. Anyways, as you will see later, this cannot actually be done).

Now will be necessary to think about the expected behaviour. As we planned (*evil laugh*), even the most naive text editor must establish some policies in order to make this work, because if it treats them as ‘mere characters’, insertions and deletions could leave the indentation of the text unpaired.

Moreover, indentation characters could be nonsensically inserted in midlines. By the way…

Where the indentation characters roam

OIL is required to be placed just after a newline, whereas with CIL is the other way around, working as a kind of graphemes from the UI point of view:

- <newline> + ►

- ◄ + <newline>

Neither indentation character can be present as a standalone character, however, multiple indentation characters can be used in a single newline:

- <newline> + ► + ► + ►

- ◄ + ◄ + ◄ + <newline>

OIL may seem special, because actually belongs to the next line. I will detail the differences later. Suffice it to say that editors just have to do the logical and straightforward thing here.

Behaviours

Cutting and pasting blocks

Think of what happens if a whole block is cutted out.

💬 *Casts ^X*:

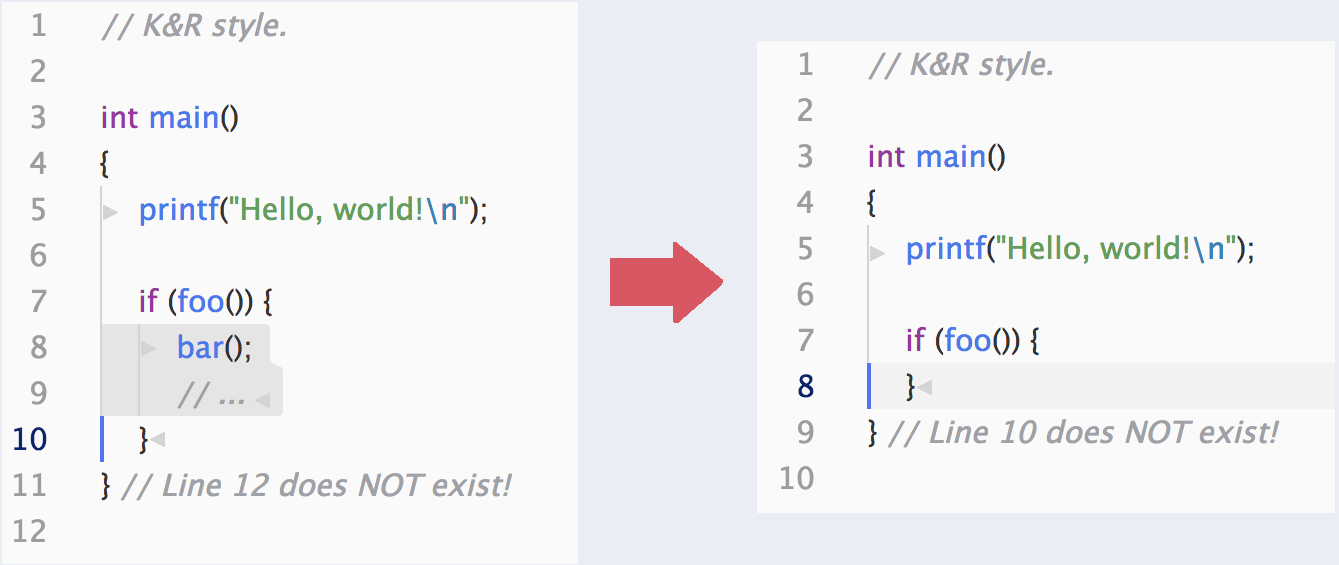

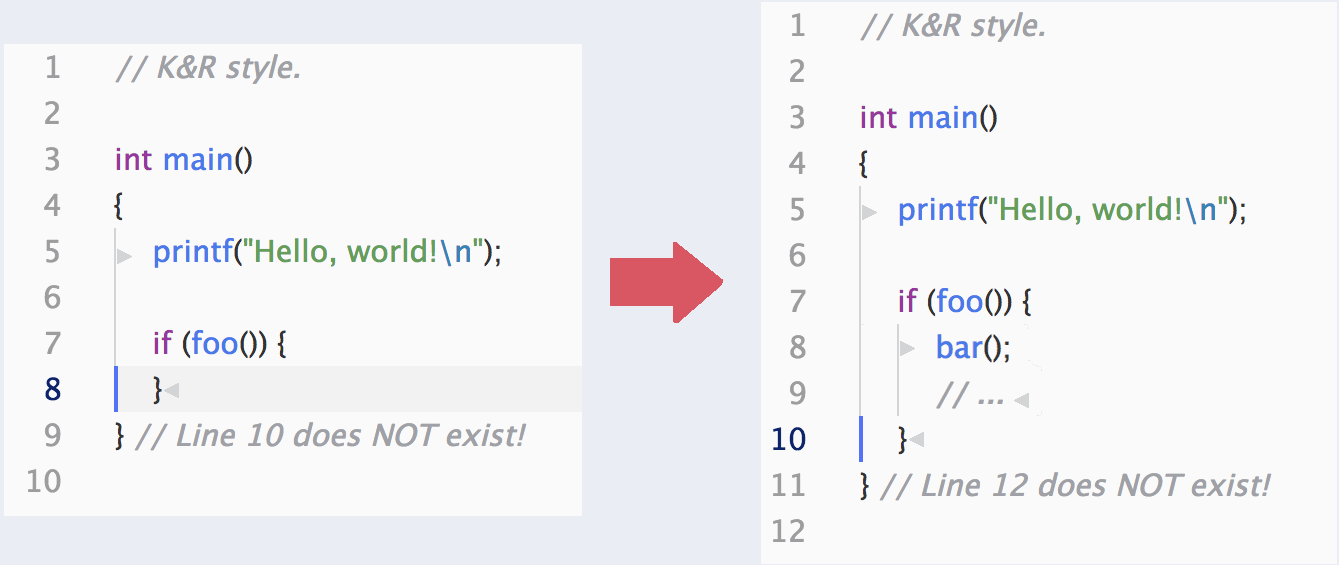

Note how the newline is included in the selection (left side).

If we paste right now, without doing anything else, what should be the expected behaviour? I’m sure we will agree on this: the text should return to its original state.

💬 *Casts ^V*:

Side note: additionally, the cursor should be placed after the end of the pasted block (the beginning of line 10). Nothing should be selected.

To make this trivially simple, OIL and CIL should be located in the first and the last lines belonging to the indented block respectively. No whitespace is encoded at the beginning of each line.

Things to note:

- Remember that an

OILcharacter located at the beginning of the buffer is regarded as if it were after the last newline of a previous imaginary buffer. - As selecting

OILorCILoutside their graphemes is meaningless, it cannot be done from the UI. OILis captured when cutting, and it is required to be pasted after a newline. What if the user places the cursor in the middle of a line before the second step?

The last question won’t be really important (as I said, this is an utopic approach). But for the sake of completeness, let’s say I don’t actually care, because can be regarded as an implementation-defined detail. Possible behaviours would be:

- Adding automatically a newline there if missing.

- Moving the cursor automatically after the end of line before pasting (if needed).

Cancellation of nesting

if True: # NL + ►

print("Hello!") # ◄ + NL

# NL + ►

# Code pasted!

print("World!") # ◄ + NL

If this is going to happen during a paste operation (CIL immediately followed by OIL), the editor must take care of removing both. This is necessary to not inadvertently break the expected behaviour, like this:

if True: # NL + ►

print("Hello!") # ◄ + NL

# More code pasted.

# Unexpectedly, now this code (and all that follows)

# is out of the conditional block!

print("?!?")

# NL + ►

# Code pasted!

print("World!") # ◄ + NL

Once the cancellation is cancelled itself in the first example, the code looks the same:

if True: # NL + ►

print("Hello!")

# Code pasted!

print("World!") # ◄ + NL

But then, the second piece of pasted code would behave as expected:

if True: # NL + ►

print("Hello!")

# More code pasted.

print(":)")

# Code pasted!

print("World!") # ◄ + NL

Note how, in this example, OIL and CIL were not exactly side by side (there is a blank line in between). This is because blank lines are also allowed, making the nested block as elastic as this rule 😉.

Cutting and pasting text inside a block

if True:

if True:

print("Hello")

# Paste it below!

# End of the block.

if False:

# Cut the next line!

print("World!")

If it contains full blocks, the rules explained in their section have to be honored). This is not actually an special case, and the behaviour with block-level text is trivially guessed: if something is cutted from a block and pasted to another, that something must be at the level of the new block.

if True:

if True:

print("Hello")

# Paste it below!

print("World!")

# End of the block.

if False:

# Cut the next line!

There is no indentation to correct. Once the text is inside the block, it is enclosed in the indentation level of the block. If the line must be restored to its original location, it is just the same.

Breaking indentation

There is a scenario where the editor must stablish a special policy: a unpaired text is cutted or copied.

The general rule is that the editor must add the pairs to the orphaned indentation characters, both in the source and in the copy buffer.

There is only one exception. If the copy buffer starts or ends with an unpaired indentation grapheme, that one must be removed.

This is easy to understand:

if True:

if True:

print("Hello")

# Cut the next **or** the previous line!

print("World!")

if True:

# Paste below!

Without the exception, the result could be:

if True:

if True:

print("Hello")

# Cut the next **or** the previous line!

if True:

# Paste below!

print("World!")

Because we carried one extra level of indentation. What we actually expect is this:

if True:

if True:

print("Hello")

# Cut the next **or** the previous line!

if True:

# Paste below!

print("World!")

The only tricky part: as it was pasted after a CIL, it is moved after the block. OIL also has some special rules to consider.

The opening grapheme(s)

The ‘<newline> + N * OIL’ combination is treated as a kind of grapheme. But OIL is special here, because as far as the editor is concerned, it also forms a grapheme with its following grapheme (even whether it is its closing pair!).

The key special behaviour of this character is the one triggered when the previous newline is removed, in which case:

- The

OILremoval is not implied (does not belong to the same line). - If it is removed in such a way

OILwill be located after another newline, both will form a new grapheme together. OILwill be moved to the next line otherwise.

If a whole line or block is removed, the second remark will apply. Otherwise, the line which contains the OIL character will be combined with another (that character must be removed, and the editor is responsible to pair the orphaned CIL including the following lines).

Let’s remap our keyboard

Watch at your tab key (⇥). When you press shift, it also can be used to remove levels of indentation (⇤). This is somewhat inconsistent, because tab characters are allowed in the middle of a line, so they are not equivalent.

On the other hand, some text editors include a pair of keyboard accelerators to increase the indentation level (even from the middle of a line): ^ + [ and ^ + ].

How many often you have to use tabs in the middle of a line? Some people even are using the tab key to write spaces, not having a dedicated key for tabs!

This is not mandatory to use this kind of text editor, but since we are dealing with it, let’s remap the keys to increase the usability.

Now:

- ⇥ is remapped as ► (same behaviour as the old

^ + ]). - ⇤ is remapped as ◄ (same behaviour as the old

^ + [). ^ + [is no longer necessary.^ + ]is remapped to insert tab characters only.

Hereafter the tab key is called the indentation key.

The indentation of a line is not a grapheme

With this model, that space at the left side of a line cannot be selected from the editor. It also cannot be ‘removed’, unless the whole block is removed with it.

However, indentation can be manipulated through the indentation key (or through ^ + [ and ^ + ] if you use the ‘classic’ key scheme). Place the character on a line or select a fragment which spans through several lines, it will do the trick.

To be continued

In this part, I established some behaviours which could be the solution, but cannot actually be implemented. In the next part I’ll debunk them… and present a working variant.

Update 1: added example of the issue with ‘cancellation of nesting’.